Flower power: an interview with Joy Gregory

In this excerpt from In View, Rachel Potts speaks to artist Joy Gregory about how working with plants has helped her to deal with the stresses of the pandemic.

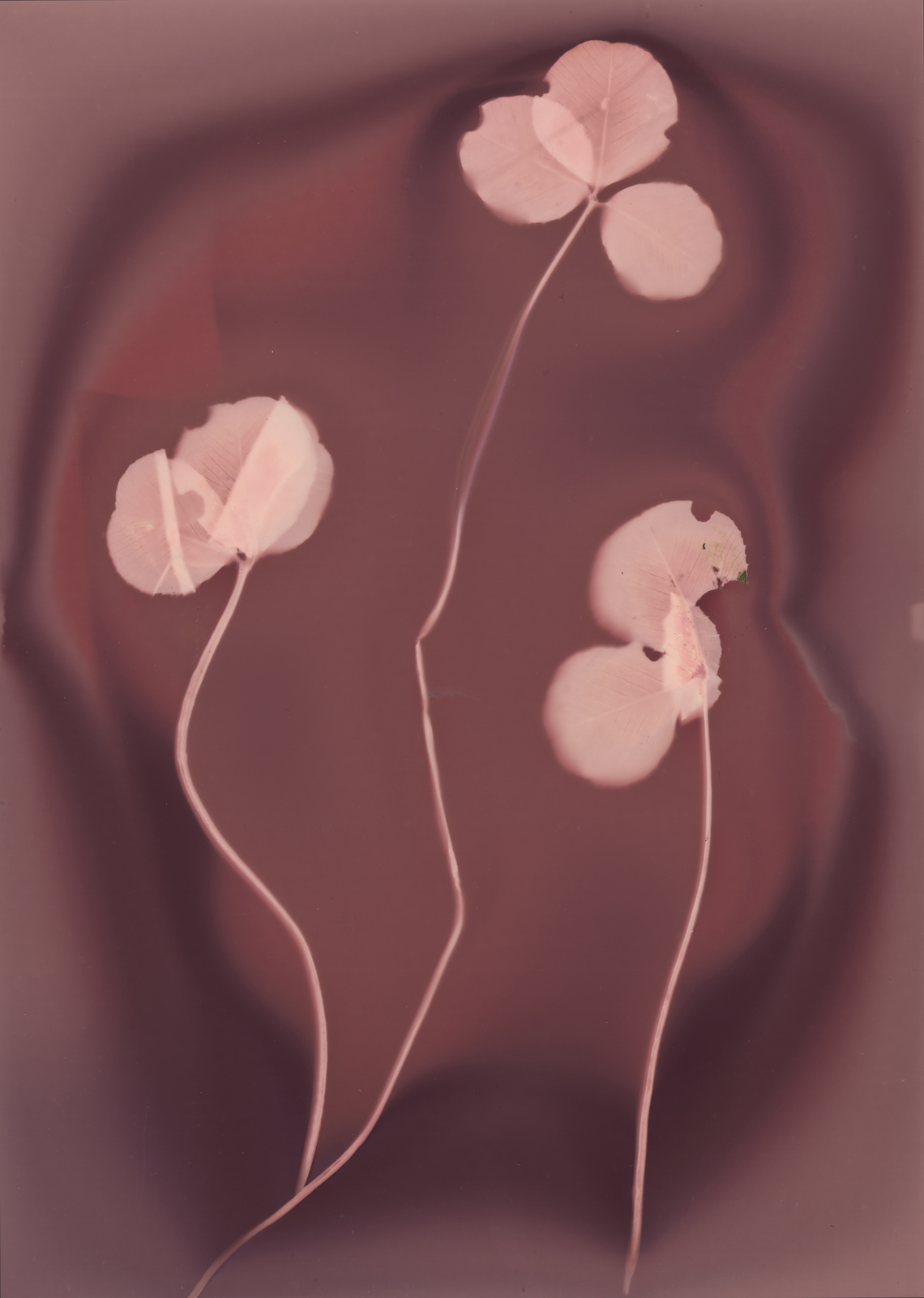

The lumen print of a clover plant made by Joy Gregory on show in the exhibition Unearthed: Photography’s Roots may appear almost timeless, or out of time. In fact, it is very much a product of 2020, and made by an artist sensitive to the threads that link nature and human culture – perhaps one of the most urgent topics of today.

Gregory, a British artist known for using early photography and other media to subtly explore political and cultural realities, created this piece using a process that dates back to experiments from the 1830s. It involved placing a clover stem on paper, which had been sensitised to light with a silver-gelatin coating, and then exposing it to sunlight to capture a negative image. Though this is Gregory’s sole work in Unearthed, it was made during the first lockdown of 2020 among a series of other prints of plants collected on daily local walks in south London, using old photographic paper she had to hand. The halo that appears around the clover is produced by the silver on the paper’s surface reacting with moisture from the plant – what she calls “its last breath”.

At that point in the year, an outing to the park meant something new. “This thing had arrived that could destroy us,” says Gregory. “And then every evening we’d watch the television and there’d be these horror stories unfurling. My generation and others, I don’t think we’ve actually lived with that sort of terror.” The act of picking plants and recording them gave her “something to do each day, gave me a purpose, which kept me safe mentally”.

Gregory also found comfort in the fact that plantlife literally sustains humans – by producing oxygen, for instance. She documented the plants with appropriate thought and care – first using an app to identify her specimens, and then incorporating their names and the dates they were found into each print’s title. This scientific approach “was like taking control, or trying to, while being immersed in nature”.

Her lockdown prints grew into the project The Life Force of Plants, which pairs notes on species’ nutritional and medicinal value – and their native origins – with lumen prints and cyanotypes (a process also using UV light, but reacting with iron salts to create vivid blue results; literally blueprints). Clover, for instance, is protein- and vitamin-rich, and has been used as an eyewash. The works were displayed last autumn at a show in west London organised by collector Eiesha Bharti Pasricha, to provide something positive for the community “in the shadow of Grenfell”. It also featured work by the Gambian-British artist Khadija Saye, who was killed when the tower block caught fire in 2017.

Gregory emerged as an artist during the Thatcher years, when politicised Black British practice was blossoming. Her late-80s Autoportraits reclaimed conventions of mostly white women’s magazines; for The Handbag Project, 1998, she made salt prints of expensive handbags sourced during a residency in Cape Town when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings were unfolding. She is also an educator – she’s currently a lecturer at Camberwell College of Arts, and she has run workshops and collaborations with communities across the globe, from the Orkney Islands to Sri Lanka. The Life Force of Plants was about healing and sustenance but also highlighted that botany is not apolitical. Many plants “are where they are because of economics”, she says. “And [it links to] why we are where we are now, and the journey of humans – all of it based on economics.”

On a research trip across the Caribbean in the 1990s, she became interested in the plant medicine that her Jamaican parents had practised, and then the truth about supposedly native flora. Considered typically Caribbean, breadfruit was in fact brought in from the South Sea islands “to feed the slaves”, says Gregory. “It has almost every mineral and vitamin that you need. And so if you want to keep the costs of your workforce down to virtually zero...”

She also looked into the collector Hans Sloane, who flourished from the 1680s as physician to the then governor of Jamaica. The activity of Sloane and his contemporaries “is still part of our lives”, says Gregory. “A lot of the plants in Kew Gardens were stolen,” while the British Museum and the Natural History Museum are founded on his holdings.

The Life Force of Plants reveals that the Hollyhock, a staple of the English country garden, is native to Asia. It probably arrived in Britain via Palestine in the time of the Crusades. The series exemplifies how Gregory’s use of Victorian photographic techniques results in ethereal, frequently beautiful prints that carry their subject matter lightly. As curator Anne McNeill has written, Gregory’s work explores inequities or marginalisation “in such a way that is never confrontational”.

This article was originally published in our Friends' magazine In View, which also includes the latest news from the Gallery, a closer look at some of our favourite artworks from the Collection, and an interview with Dulwich and West Norwood MP Helen Hayes.

To read the full article, pick up a copy of In View on your next visit to the Gallery or join as a Friend to receive yours free in the post.

Image: Joy Gregory, Clover, 2020, unique lumen print (gelatin silver), 127 x 178 mm. © Joy Gregory.