Machine-age modernists: Claude Flight, Cyril Power & Sybil Andrews

The revolutionary printmakers of the Grosvenor School of Modern Art were an unlikely band of aspiring artists drawn from diverse backgrounds. Significantly, three of the school’s key figures – the visionary linocut artist Claude Flight and his most successful pupils Cyril Power and Sybil Andrews – were active participants in war work during World War I. Bucking the artistic trend for a reassuring post-war ‘return to order’, the trio were obsessed with the relentless pace of the machine age, and the necessity of creating a ‘real and vital art of to-morrow’ which could capably reflect it.

Claude Flight

Claude Flight came late to the art world. Following an eclectic career which included stints as an engineer and beekeeper, he enrolled at Heatherley’s School of Art where he met C.R.W. Nevinson, a champion of the Italian Futurist movement, which was to have a major influence on Flight’s work. His studies were interrupted by the War, during which he served in France as a farrier, eventually receiving the Mérit Agricole.

“Time seems to pass so quickly nowadays…this speeding up is one of the psychologically important features of today."

After returning to his studies, Flight became obsessed with linocut printmaking, which was still looked down on in some artistic circles since it was used as a teaching method for schoolchildren. The innovation of Flight and his pupils was to transform the humble artform into something powerfully modern. In 1925 Flight observed “Time seems to pass so quickly nowadays…this speeding up is one of the psychologically important features of today." The rhythmic patterns which he favoured seem to reflect both the chaotic pace of modernity and broader intellectual currents, including the revelations of Einstein’s Theory of Special Relativity which had thrown out commonplace assumptions about the fixed nature of time and space.

As the home of the Grosvenor School, machine-age London and its cutting-edge transport system was the perfect subject for Flight’s dynamic rhythms. Pictured above, Speed was created by the artist in 1922. Depicting buses rushing down Regent Street, the warped lines representing the buildings and vehicles create an almost hallucinatory impression of bustling modernity.

Cyril Power and Sybil Andrews

Cyril Power spent much of his life as a practicing architect before he was called up to the Royal Flying Corps in 1916. A chance meeting was to prove decisive on his career after the war. After returning to his wife’s hometown of Bury St Edmunds, he met Sybil Andrews, who became his student and artistic collaborator. Like many women of her generation, the War created new opportunities for Andrews – her work constructing aeroplanes in Bristol enabled her to begin formal art training through a correspondence course.

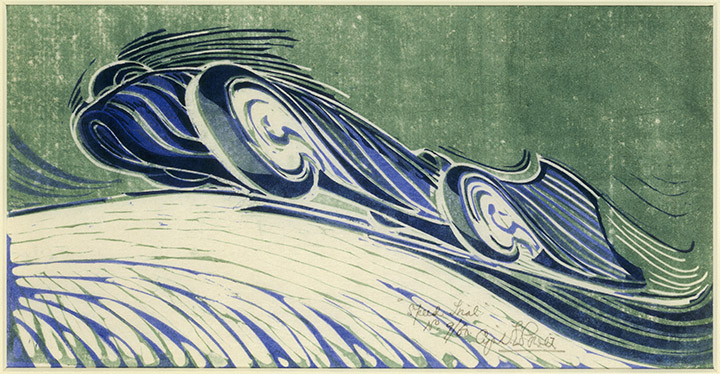

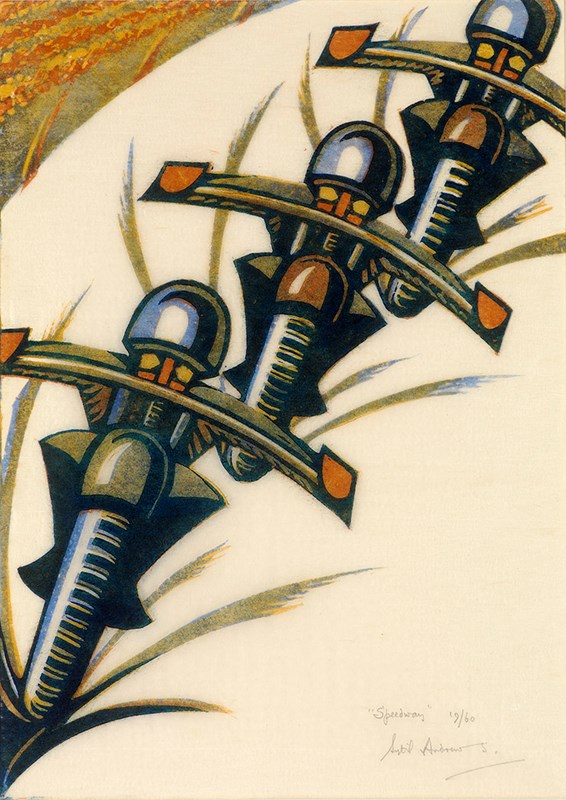

In 1922 Andrews and Power moved to London to pursue their artistic careers proper. They enrolled at Heatherley’s School of Fine Art, and were subsequently appointed as staff at the Grosvenor School. Attending Flight’s classes between 1926-1930, both artists produced work which aimed to be radically modern. The record-breaking Bluebird Car depicted by Power in Speed Trial recalls the Futurist Manifesto’s fantasy of ‘a racing automobile with its bonnet adorned with great tubes’. Andrews’ Speedway goes further, depicting three motorcycle racers whose hunched figures and mechanoid headgear suggest a fusion of man and machine.

‘A real and vital art of to-morrow’

Despite these resemblances, Flight, Power and Andrews differed subtly from the Futurists, whose glorification of speed, violence and extreme subjectivity had taken on a sinister edge after the War. The perspectives of Speed Trial and Speedway are firmly in the context of mass entertainment, in keeping with Flight’s declaration that ‘individual expression of individual emotion has no place in our modern industrial development’.

Elsewhere, the trio explored the new age of mass transit, representing the universal experiences of commuters. Buried in their newspapers, the disengaged passengers in Power’s Tube Train display a typical English reserve, despite the fact that their tube carriage appears to be warping through time and space. Like the early films of Hitchcock, Power seems intent on expressing the tedium and alienation created by modern urban life.

Part of Flight’s reasoning for favouring the linocut was its democratic potential. He hoped the affordable art form would enable people of average incomes to achieve aesthetic fulfilment in a way that was denied to them due to the high cost of fine art. Sadly, this mass audience for linocuts never emerged, and the Grosvenor School artists rapidly fell out of favour after a brief period of success in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Power and Andrews came closer than any of their peers to achieving Flight’s utopian ideal, producing posters for the London Passengers Transport Board from 1929 to 1937 under the pseudonym Andrew-Power. Reflecting the exciting range of sporting events which could be reached by the Tube, they celebrated the new age of leisure. For much of the London public it was a breath-taking first encounter with modernist art.

View all of these artworks, and over a hundred more from the Grosvenor School at our Summer exhibition, Cutting Edge: Modernist British Printmaking. Until 8 September.

Images from top: Cyril Power, Speed Trial, c.1932, photo Osborne Samuel Gallery London / © The Estate of Cyril Power. All Rights Reserved, [2019] / Bridgeman Images, Claude Flight, Speed, 1922, © The Estate of Claude Flight. All Rights Reserved, [2019] / Bridgeman Images/ photo Photo © Elijah Taylor (Brick City Projects), Sybil Andrews, Speedway, 1934, Photo Osborne Samuel, London/ © The Estate of Sybil Andrews, Cyril Power, The Tube Train, c.1934, Photo London Transport Museum Collection/© The Estate of Cyril Power. All Rights Reserved, [2019] / Bridgeman Images, Andrew Power, Wimbledon, 1933, © The Estate of Cyril Power. All Rights Reserved, [2019] / Bridgeman Images/ © The Estate of Sybil Andrews © TfL from the London Transport Museum Collection.